Stone Farm: For half of a century.

If you take care of the land,

the land will take care of you.

We’re trying to raise you a good horse.

We sell only what we raise.

The horse resides in a new, four-stall barn where he can see the various comings and goings – equine, human, vehicular – at Ashwell Stable. Park your car up that way, and he’ll almost always hang his head over the stall door. You pretty much have to say hello and give him a pat on the neck. For him, for you, for anyone who ever hurt. That’s just the way Mandola is.

In the first race Sept. 2 at Saratoga, the then 5-year-old gelding fell over the last fence. He was making a run, charging toward the front and looking like a winner. He was in with a shout inside the eighth pole, which is all anyone ever wants at Saratoga. Then, in a moment of indecision at takeoff time, he fell. Hard. He and jockey Willie McCarthy sprawled, splayed and skidded to the turf. Mandola nearly saved it, but slid to a stop after pitching right and ultimately rolling left.

He got to his feet and rode in the horse ambulance back to trainer Jonathan Sheppard’s barn at the Oklahoma Annex. There, the diagnosis looked bad.

[Mandola greets a visitor at Ashwell Stable. Nolan Clancy photo]

Six days after losing Divine Fortune in a fall at the same fence, the Sheppard crew braced for more terrible news. Like Divine Fortune, Mandola had injured his shoulder. Unlike the 2013 steeplechase champion, Mandola could stand somewhat comfortably, even walk a bit. His left shoulder was sore and swollen. If it was broken, he probably couldn’t be saved. If it was a muscle injury, something involving a nerve or a ligament, he might have a chance.

Mandola, owned by Arthur and Staci Hancock’s Stone Farm, would make the most of it.

He survived the first night and greeted visitors with a depressed but, “Hey, it could be worse,” attitude while eating hay at the stall door the next morning. On Twitter, he was reported as being euthanized. If a horse could use social media, Mandola might have gone all Mark Twain: “Reports of my death have been greatly exaggerated.”

Six months later, he’s still defying exaggerators – not that it was easy.

Mandola spent a few days in Saratoga, where he kept eating and remained comfortable. He improved enough to make Sheppard send him home to Pennsylvania.

“He was pretty comfortable at Saratoga, he was on Bute (an anti-inflammatory) and considering what happened he wasn’t too bad,” said Sheppard assistant Keri Brion. “When he got off the van at home, he was stiff and sore which is pretty understandable too.”

Veterinarian Dr. David Levine, who works out of the University of Pennsylvania’s New Bolton Center nearby, saw Mandola a day after he arrived.

“Dr. Levine picked up his leg, pulled it forward, pulled it back, rotated it side to side and the horse didn’t seem to really mind,” said Brion. “He thought it was a serious nerve or a muscle type of thing.”

Levine wanted more information, though, and put New Bolton’s diagnostic tools to good use. The scans brought bad news. Mandola’s left shoulder, specifically the superglenoid tubercle at the front of the shoulder, was broken. He faced several options, none of them all that good.

“We spent some time talking about the options for him – surgery, doing nothing, euthanasia,” said Levine. “It was going to be challenging surgery. He had big fragments, a lot of them, and they weren’t able to be reconstructed and put back together. You worry about recovery, you worry about how much nerve damage there is, you worry about the healing process afterward.”

Surgery, the New Bolton team figured, was the best choice. Left alone, the fragments would cause arthritis, decrease range of motion and limit Mandola’s quality of life. Despite all the technological improvements, there was no way to repair the fragments with screws, plates and wires. There were too many, too involved with the joint. Removal became the only medical choice.

Though they studied it, the decision was simple for the Hancocks.

“I guess it comes down to if you’re in this business to raise horses and have horses or you’re in this business to make a business of it,” said Staci. “There was no question, as long as the vets didn’t think we were asking too much of him, we were going to give it a shot. If they gave us another answer, we wouldn’t have gone through it.”

The Oct. 1 operation required three surgeons and took about two hours. The process involved a big incision, isolating a nerve as thick as your finger, pushing through muscle and tendon.

“One of the most important and biggest tendons in the body called the biceps brachii runs through there,” said Dr. Mike Ross, who worked on Mandola with Levine. “It’s huge and wide and it’s one of the things that made this surgery challenging – the sheer volume of it. It’s this huge muscle that’s very important for form and function.”

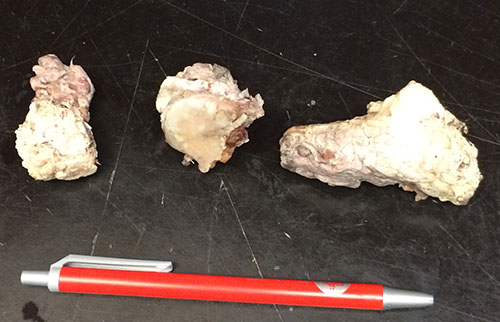

The surgeons identified the super scapular nerve, cut the tendon away from the bone fragments, and filled a small bowl with nuggets of bone – one almost 3 inches long. Levine keeps them on a shelf in his office.

“Based on experience and working on other parts of the body when you have numerous fragments it’s better to take the fragments out and allow the tendon to re-attach to the exposed bone,” said Ross. “What we’re hoping Mother Nature does is help this disorganized fibrous tissue reorganize to a functional biceps brachii tendon.”

Once the fragments were gone, surgeons closed the incision and prepped Mandola for recovery. Often as daunting as surgery itself, recovery challenges horses. They must emerge from anesthesia, stand on the injured limb and not lose their cool in the process. Despite it all, Mandola sailed through.

[Above: Three bone fragments – with a pen for scale – removed from Mandola’s shoulder. Joe Clancy photo]

“He rolled over, got up with his good leg, dangled that leg for a minute and then was like ‘Oh, I can stand on this.’ ” Levine said. “You don’t know how much nerve damage he had. You’re doing all that dissection, you hold up that nerve. You expect the nerve to be not damaged but inflamed. He actually walked quite well on it though.”

Though he prepared them for disappointment, Levine loved making a positive phone call to Mandola’s connections. The veterinarian also paid special credit to his patient.

“He’s such a calm, awesome horse and that helps,” he said. “You ask him to do something, he does it. You can do anything with him. He was lame for quite a bit of time. He didn’t use that leg for quite a bit of time. You get lucky sometimes, but it helps to have the right kind of patient. His attitude is what prompted them to save him in the first place and it surely helped him in his recovery. He’s a cool horse, which only helps.”

The opinion did not surprise Arthur Hancock. As a yearling, Mandola went endured various treatments for an abscess on the top of his head. It lasted months, and kept him out of the yearling sales.

“We couldn’t get it to heal and I’d never had a horse have something like that,” he said. “We tried antibiotics, Furacin, all kinds of things. Finally Dr. (Bob) Hunt at Hagyard told he was going to try something.”

Hunt’s something involved putting live maggots in the wound. The maggots worked, the infection cleared and the wound healed. Mandola endured it all.

“He’s tough, a fighter, he had to be to put up with that,” said Hancock. “That was a bad deal and it went on for three months or more.”

After his shoulder surgery, Mandola stayed at New Bolton for five days, and steadily improved. His other foot held up, no laminitis developed, and he went back to the farm. Step one was stall rest, loads of it. The staples came out two weeks after surgery. Then came hand-walking. A month into that, he went lame. Levine took follow-up X-rays, which were clear of bone fragments. The veterinarian blamed healing and some nerve pain and prescribed acupuncture therapy.

“He took a turnaround from in pain to striding out and looking much better after one treatment,” Levine said. “It might have been the acupuncture, but it also might have just been the healing process too.”

Regardless, Mandola went back to improving. He came off anti-inflammatories, jogged sound and just recently started getting turned out in a pen.

“I saw him the first day he was turned out and at first he just stood there,” said Bailey Poorman, who works with Brion at Ashwell. “Then the horse next to him did something and he jumped a little bit and you almost see him go ‘Heyyy, I’m free.’ One of his favorite things in the world is to roll and he threw himself into a roll and did this spider dance with his front legs, jumped up and started squealing. I was so happy for him.”

There’s a lot of that going on when it comes to Mandola, a Kentucky-bred son of Bluegrass Cat and the Hancocks’ Clever Trick mare Vickey’s Echo.

“I’ve given that horse many a hug,” said Levine. “His personality and who he is helped us every step of the way.”

When he started on the surgical path, Levine hoped to save Mandola, and find him pain-free days for a life of retired turnout in a field somewhere. A future use as a riding horse was way down the list. Racing again wasn’t even a thought.

“Our success was measured in, will he survive?” he said. “Anything else is gravy. I think we’ve had a great success.”

But he’d sure like some gravy. All being well, Mandola will start being ridden in June. The controlled exercise will be good for him, and will go a long way to regaining some muscle in his shoulder.

[Mandola stands tall, injured left shoulder and all. Nolan Clancy photo]

“I’m not going to put him on the track galloping anytime soon, but they’ll do some walking, jogging, go up through the woods like they do with all of them,” Levine said. “When we made the decision to do surgery, they wanted to try to maximize his comfort and, though it might have been pie in the sky at the time, maximize the chance that he could return to some form of work.”

Now, Levine won’t rule out a return to racing.

“He’s still retired. The goal is . . . there’s no reason why he can’t do things. Would I be surprised if he went back to racing? Yes.”

But the veterinarian won’t cross it off the list. Not now, not with Mandola.

“David says everything from the first day it happened has helped,” said Sheppard. “The horse made so light of it that we thought there was some nerve damage, not a fracture. It turned out to be far worse than we realized. At first, they said if we were lucky we might be able to save him as a lawn ornament, now he’s saying it’s conceivable he might be able to race again not that we’re going to push it. We’re in no rush.”

NOTES: Mandola won once on the flat, going 1 1/4 miles on the synthetic at Arlington Park, for Stone Farm and trainer Mike Stidham and became a steeplechaser after getting a test over some straw bales in the Stidham shedrow . . . For Sheppard, Mandola lost three flat tries (including a second at Delaware Park in May 2014) before winning his hurdle debut in October 2014. He won again to start 2015 and placed in two novice stakes before the fall at Saratoga.