Stone Farm: For half of a century.

If you take care of the land,

the land will take care of you.

We’re trying to raise you a good horse.

We sell only what we raise.

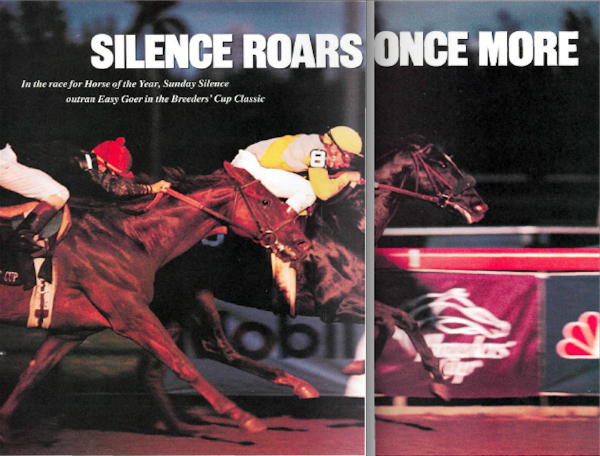

In the race for Horse of the Year, Sunday Silence outran Easy Goer in the Breeders’ Cup Classic.

Chris McCarron, the reins taut in his hands, sat like a statue on the back of Sunday Silence, rocking only slightly as he bent forward in the saddle and waited for Easy Goer. McCarron was not the only one waiting for Easy Goer at 5:37 p.m. last Saturday. At that moment the field of eight horses had straightened out along the backstretch at Gulfstream Park and had begun racing through the sixth furlong of the 10-furlong Breeders’ Cup Classic, looking like a cavalry troop racing cross-country, stretched some 20 lengths along the track. This was precisely what everyone in racing had long been waiting for: It was a showdown between America’s two best horses, with the title of Horse of the Year at stake, all wrapped in a race designed specifically to reveal the fastest, finest racehorse in the land.

Now, suddenly, the chestnut Easy Goer was gaining speed on the outside. As the odds-on favorite surged forward, the crowd of 51,342, strangely subdued through the first half mile of the race, began to quicken and sent up loud cries: “There he goes!” It was thus, in the dimming light of a late Florida afternoon, that arguably the most dramatic moments of the decade in racing began.

Sunday Silence was lying third, behind front-running Slew City Slew and Blushing John. McCarron, who knew that Easy Goer would be coming any time now, looked up as they raced toward the far turn. Slew was out there winging it under jockey Gary Stevens, on his way to racing six furlongs in a dashing 1:10[2/5], and had two lengths on Blushing John, with Angel Cordero Jr. hanging on. Easy Goer had been lying sixth around the first turn and had appeared to be struggling during the first three furlongs, striding as if climbing with his front legs, in the way of a horse who doesn’t fancy the surface. But once the Goer straightened out on the back-stretch, he settled into his long, rhythmic stride.

Easy Goer’s jockey, Pat Day, did nothing, letting the colt settle on his own. “When we turned into the back side, the colt really leveled off and dragged me into contention,” Day said.

Picking up speed, Easy Goer swept into fifth position down the backstretch, and McCarron was now listening for him on his outside. “I heard him coming at the half-mile pole,” McCarron said. “I was kind of expecting him. So I glanced over and saw a chestnut—I assumed it was Easy Goer.”

It was. Day figured he was in a perfect spot, ready to pounce. Heading for the far turn he had an armful of horse under him, and there were still 900 yards to run. He figured he could follow right on the tail of Sunday Silence until the final 400 yards and then blow past him. He figured Easy Goer could dominate Sunday Silence as he had in the Belmont Stakes five months before, when the Goer had spoiled the black colt’s chance to become the 12th winner of the Triple Crown. In the Kentucky Derby on May 6, Silence had whipped Easy Goer by 2½ lengths; he outgunned him again in the Preakness two weeks later, winning by a flared nostril. Then Easy Goer crushed his rival in the Belmont, winning by eight lengths and, as things turned out, setting up this final showdown of ’89 in the much anticipated Classic.

But as the horses approached the far turn at Gulfstream, McCarron had more horse than Day realized. Hearing Easy Goer moving up on his right, McCarron thrust his hands forward a notch, and Sunday Silence picked up the beat at once, edging away from his pursuer on the bend. “When Chris called on Sunday Silence then, he spurted away from us,” said Day. “I was hoping we could go with him, but when he moved away, we didn’t follow. I pushed and tapped my horse and chirped to him, but he was slow finding his stride.”

Mistakenly, McCarron thought that he had finished off Easy Goer and sensed that this richest horse race in the world, with a winner’s purse of $1.35 million, was his. Just as mistakenly, Cordero was thinking he was riding the winner as he sent Blushing John after Slew City Slew and swallowed the leader in a few quick gulps of ground past the three-eighths pole.

“I thought I was going to win it when I passed that horse,” said Cordero. “I hadn’t even asked him to run. It was so easy.”

Stevens, aboard Slew, thought too that Cordero had won his first Breeders’ Cup Classic. “When Blushing John hooked me, I looked over and saw him and thought, Here comes Angel! He’s gonna win it. He had a real good hold of his horse.”

Two strides later, as Cordero rushed away from him, Stevens glanced over again and there was Sunday Silence, striding boldly against the bit for McCarron. “He passes me too, chasing Angel,” said Stevens. “Then I look over again, and here comes Pat on Easy Goer. He was riding that horse like hell.”

By now the grandstand and the jerry-built bleachers erected to accommodate the crowds were vibrating in the din as the horses rounded the final turn. Blushing John, who was nearly 22-1, was still feeling like a winner to Cordero. But as he peeked over his right shoulder, Cordero saw that distinctive black head with the little white kite on the forehead. Cordero did a double take. “I thought. Oh, no! Here’s the big little horse. All of a sudden Sunday Silence was right there next to me.”

Just behind the leaders, Day had gone to the whip on the turn and was driving Easy Goer forward. But the horse was having trouble staying in the chase, a consequence perhaps of his recent racing schedule. Trainer Shug McGaughey ran Easy Goer four times between the Belmont and the Classic, first winning the 1⅛-mile Whitney and the 1¼-mile Travers at Saratoga and then the 1¼-mile Woodward Stakes at Belmont Park. At the time of the Aug. 19 Travers, McGaughey had shown little inclination to run Easy Goer in the 1½-mile Jockey Club Gold Cup on Oct. 7 at Belmont. Sometime after the Sept. 16 Woodward, however, he changed his mind.

This came as no surprise. After all, Easy Goer’s owner, Ogden Phipps, is a former chairman of The Jockey Club, after which the race is named; his son, Ogden Mills Phipps, is the chairman today. Over the past few years, faced with competition from the richer Breeders’ Cup Classic, the Gold Cup’s prestige has waned, and it certainly would have been a further blow to its reputation had Phipps chosen to pass up the race with his champion horse.

In the end, Easy Goer beat six ordinary horses in the Gold Cup, winning by four lengths and earning $659,400 for his exertions, but that victory may have exacted a dear price. It meant that Easy Goer would be coming to the 10-furlong Classic off the 12-furlong Gold Cup—a potentially tricky parlay for a trainer, because the longer race can have the dangerous effect of dulling the colt’s natural speed, of blunting the quickness that he might need in the shorter race.

In contrast, trainer Charlie Whittingham had run Sunday Silence only twice in the five months since the Belmont, both times over a 1¼-mile distance—in the Swaps Stakes at Hollywood, where he finished second, and two months later in the Sept. 24 Super Derby at Louisiana Downs, which he won by six. Time and again, the 76-year-old Whittingham has shown that there is no trainer more adept than he at preparing a horse for a single goal over an extended period of time. In the week before Breeders’ Cup Day, he was plainly buoyed by what he perceived to be his advantages going into the Classic.

“My colt will win,” Whittingham said on the eve of the Classic. “He’s fresher than Easy Goer, he’s quicker, and I know from experience that the longer races are harder on a horse than the shorter ones. Easy Goer just had a long one. You don’t get over them so easy.”

Whatever the reasons, when McCarron put his hands forward and Sunday Silence dashed away from Easy Goer into the turn, there was no denying Whittingham’s point that Easy Goer’s chances in the Breeders’ Cup Classic—and hence his bid to be voted Horse of the Year—may have been compromised by his efforts in the Gold Cup. Turning for home, Sunday Silence had to beat only Blushing John and Cordero, who screamed at his mount and pumped on him as Sunday Silence drew alongside. “Come on, Johnny!” he shouted. “Go on with it, Johnny!”

For all of Cordero’s whooping and hollering, Blushing John could not hold on. From the quarter pole to the stretch, Sunday Silence whittled into his lead, with McCarron tapping his colt lightly on his shoulder, pushing on him and waving the stick in front of his left eye. Sunday Silence has never responded well to the whip, and Whittingham had instructed his jockey accordingly. “Charlie said to use the stick only as a last resort,” McCarron said.

He did not use it even then, despite the fury of the final drive. At the eighth pole, with 220 yards to the wire, Sunday Silence was pinning his ears as he pulled away from Blushing John and took off for the wire in the gathering dusk. It was so dark by the time they ran the Classic, the final event on the seven-race Breeders’ Cup card, that Gulfstream officials had turned on the lights to illuminate the wire for the photo finish camera. As Silence raced for the wire, the crowd grew frantic, the noise deafening.

Out of this eerie twilight, on the outside, Easy Goer emerged to make a last, desperate run at Sunday Silence through the final 110 yards. Cordero, still hoping for second, saw Easy Goer first. “He was like a giant swooping down on me,” said Cordero. “But he was going after Sunday Silence, and I just watched them run to the lights at the wire. A great race!”

McCarron couldn’t believe what he saw in those final yards. “I felt I had the race won,” he said, “and then I saw Easy Goer again. I thought I’d put him away leaving the half-mile pole. I thought. Here he comes again! But I didn’t hit my horse. I just kept shaking the stick.”

Easy Goer was two lengths back, but he was running at Sunday Silence in long, devouring jumps. “He finally found his stride,” Day said. “I thought we could catch him. I never gave up on him.” He was a length behind with 30 yards to go. Then half a length. With 10 yards to go, Easy Goer was closing with a rush, and a good many of the bettors in the place were leaning toward the wire with him, like so many palm trees bending in the wind. But in the final jump, under the yellow beam shining across the track, Easy Goer fell a neck short. The winning time of 2:00[1/5] represented an extremely fast performance on this track.

It was a tremendous horse race. Up in the box seats, Arthur Hancock, one of the three owners of Sunday Silence, knelt in front of his seat in a prayerful pose with his hands clasped over the railing, then rose to embrace his wife, Staci. Sunday Silence was born and raised at the Hancocks’ Stone Farm in Paris, Ky., and on a day dedicated to the business of thoroughbred breeding, Hancock was a winner in more ways than one: He now not only owns half of a Horse of the Year, but he also stands the colt’s sire, Halo, at Stone Farm. The way his year is going, Halo could end up as the nation’s leading sire in money won by his offspring, a much-coveted achievement for a farm in the Blue Grass.

Ultimately, though, this was Whittingham’s hour. Since those stunning defeats in the Belmont and the Swaps, he meticulously charted his plan to bring the colt to the Breeders’ Cup Classic. After the victory, horseplayers and horsemen alike feted him. From the second-floor balcony of the clubhouse, bettors called and chanted his name. He waved to them and winked at a friend. “If I ran for governor of Florida now, I’d probably get elected,” he said. On his way back to the barn to see his weary colt, he spotted trainer John Gosden.

“We caught him, John!” Whittingham yelled.

“You caught him just right,” Gosden said. Then, speaking for all his fellow horsemen, Gosden added, “Brilliant stuff.”