Stone Farm: For half of a century.

If you take care of the land,

the land will take care of you.

We’re trying to raise you a good horse.

We sell only what we raise.

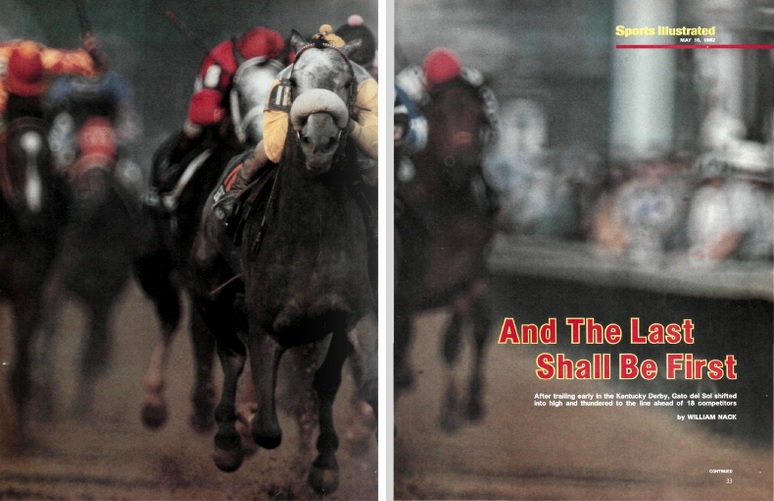

After trailing early in the Kentucky Derby, Gato del Sol shifted into high and thundered to the line ahead of 18 competitors

Trainer Eddie Gregson was walking 10 feet behind his Kentucky Derby horse, Gato del Sol, when they emerged from the quiet of the stable area at Churchill Downs and began that long trek around the clubhouse turn toward the saddling paddock. There were 141,009 people packed into the Downs last Saturday afternoon—a warm, bright day in Louisville—and thousands lined the clubhouse turn, a few yelling at Gregson as the colt strode by: “What’s the name of your horse?” And “Do you like him?”

Gato del Sol’s sire, Cougar II, the champion grass horse of 1972, had been poised and unflappable, and he passed these characteristics on, but now the colt was coming to his toes, doing a nervous little waltz, and sweat streaked his flanks. Gregson’s face was strained. This was his first Kentucky Derby, a mile and a quarter for which he had been judiciously pointing his horse for weeks, and Gato del Sol was in a sweat before he even got to the paddock.

Gregson glanced at the crowded grandstand. “It’s amazing,” he said. “I schooled this horse in the paddock, but you could school a horse every day and not re-create this. You have to have a horse physically fit to run this far in May and mentally ready to go through it. To win, it’s like climbing Mount Everest.”

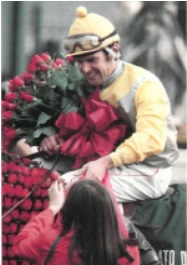

Thirty minutes later, of course, the 43-year-old Gregson found himself at the summit, for win the Derby he did. After finally settling down in the paddock and handling the raucous post parade like old Cougar himself, Gato del Sol galloped leisurely through the first part of the race with all the urgency of a kid going to school. At the end of the first half-mile, he and jockey Eddie Delahoussaye still trailed in the 19-horse field and were some 16 lengths behind the leader. Since definitive charts of the Derby were introduced in 1903, no winner had come from so far back. But the colt began picking up horses as he pleased down the back-stretch and then, rounding the far turn, bounded from 16th place to fourth in a single quarter-mile. He won his Derby right there. Outrunning Laser Light, an 18-1 shot, and Reinvested to the wire, Gato del Sol won the race—and the $428,850 first money—by 2½ lengths.

“A trainer fantasizes about this,” Gregson said. “It just bowls you over. Twenty or 30 years from now, it will make for a nice evening around the fire.”

“A trainer fantasizes about this,” Gregson said. “It just bowls you over. Twenty or 30 years from now, it will make for a nice evening around the fire.”

Gato del Sol paid $44.40 to win to the gambling clientele who preferred him, among them Arthur Hancock III, who was down for $100. He went dry-mouthed into the winner’s circle, trying to wet his lips. “I still don’t believe it,” said the Kentucky breeder, who co-owns Gato del Sol with Leone J. Peters, a New York real estate tycoon. “Is it official? Has it been declared official yet? I can’t believe we did it. It’s like a dream. My dad would sure be proud, I know that.”

It was thus that a neatly balanced gray colt, named in memory of a tan-colored cat who used to sleep in the morning sun, won the 108th Kentucky Derby at 21-1 for a trainer who was once a Hollywood actor, since reformed; a co-owner who came of age as the maverick son of the greatest thoroughbred breeder in American history; and a Cajun jockey who broke his maiden at Evangeline Downs in Lafayette, La.

Arthur Hancock came to this Derby representing the fourth generation of Hancocks to breed thoroughbreds. But until last Saturday no Hancock had ever owned the winner. Hancock’s father, the late A.B. (Bull) Hancock, is regarded by many as America’s most influential horse breeder. He was the man who turned Claiborne Farm, outside Lexington, into a showcase of the bloodstock business. Horses Bull Hancock imported and ideas he espoused would produce Derby winners Secretariat, Seattle Slew and Spectacular Bid, among others.

No one coveted the Derby more than Bull. “I saw how much Daddy wanted to win it,” says Arthur, 39, Bull’s oldest son. “We talked about it a lot. He’d plan a mating with Derby breeding, sire and dam, and then he’d get a filly or something. He had some bad luck.”

Bull’s best colt, Drone, was undefeated and training for the Florida Derby in 1969 when he broke down. Still, Bull almost won the Derby that year, when Dike got beat a neck and a half-length by Majestic Prince and Arts and Letters. But Bull would tell you that finishing third was no cigar. He died in 1972, his dream unfulfilled.

Arthur and his younger brother, Seth, ran Claiborne jointly for a few months after Bull’s death. “Then the executors decided Seth would make a better president,” Arthur says. “He was married, I was single then. He was more serious than I was. I like to shake out the straw in my stall in my own way. Seth was the right man for the job. He still is. I sort of got fired, really. I said, ‘Well, I’ll see what I can do with my own life.’ ”

Arthur Hancock established Stone Farm down the road from Claiborne and built it from nothing to what it is today—a 2,500-acre spread with 210 broodmares and nine stallions, including the 1976 Kentucky Derby winner, Bold Forbes, and Cougar II. One of his earliest backers was Peters, with whom he owns 30 mares. In fact, together they bred Gato del Sol. The colt’s pedigree wasn’t fashionable enough to get him into the posh summer sale at Keeneland in 1980. Nor did he promise to bring a big price in the fall sale. “He’d have probably brought $25,000, $30,000,” Hancock says. “We didn’t want to sell him for that. So we kept him.”

Hancock thought of the name, which means cat of the sun in Spanish. “I had a cat at the farm that would sit by the barn in the morning sun,” he says. “That image always stuck in my mind. Cougar is a cat, and the mare was named Peacefully. We named the colt in Spanish because Cougar II was from Chile.”

When Gato del Sol was 2, Hancock and Peters sent him to Gregson, who came to the racing business by way of his family’s breeding farm in Southern California, called Conejo Ranch. One of the residents there was Determine, winner of the 1954 Kentucky Derby. Gregson attended Stanford, where he eventually got a degree in Eastern European history, and for a while he considered studying law. During his freshman year he dropped out of Stanford briefly to go to Hollywood and try to get in the movies. Under contract to Warner Bros., Gregson appeared in one film, The Naked and the Dead, playing the part of a soldier who is killed by a snake. He then moved over to Twentieth Century-Fox, but the studio let him go after six months. “They gave up on me,” Gregson says. He did some summer stock, kicking around looking for work, then went back to school. “I couldn’t act,” he says. Once out of college, he also decided against studying law.

Gregson instead went to work in a cattle feed lot in California as a cowboy, but he eventually returned to the horses, his first love. He started training in 1968, and it has been his life ever since then. Gato del Sol had his moments as a 2-year-old—he won only two of eight races as a juvenile, but one was the Del Mar Futurity—and he finished the year with earnings of $220,828. Gregson had seen Cougar II win in California, and he was struck by the similarities between father and son.

“Gato del Sol has the same runnning style, the same high action in front,” Gregson says. “This horse also has the most beautiful eyes in the world.”

More to the point, the colt appeared to have inherited from his sire the capacity to go a mile and a quarter. Not that Gato del Sol was any world beater in his four previous races this year. After finishing third in the first, at Santa Anita on Feb. 25, beaten 3¼ lengths in a sprint, he lost by just a neck in the 1[1/16]-mile San Felipe Handicap, closing ground through the stretch. Under the circumstances, it was a sharp performance.

“He stumbled at the start and sprung a shoe,” Gregson says. Advance Man hung on to win. Two weeks later, in the 1⅛-mile Santa Anita Derby, Gato del Sol again made up ground through the lane, but wound up fourth, beaten 3¼ lengths by Muttering. Gregson wasn’t happy. “It was a disappointing race,” he says. “He dropped back and didn’t kick in like he does. And he had to go around horses.”

XYZ

But the colt was Derby bound, with a stop at Keeneland for his final prep in the Blue Grass Stakes. With Gregson’s eye on the Derby nine days later, a prep is precisely what the nine-furlong Blue Grass proved to be. Gato del Sol finished second, 5½ lengths behind Linkage, but Gregson liked the race. “Linkage had it all his own way,” he says, “and my horse wasn’t trained to be his fittest for that race. I wanted something left.”

In his final work on Thursday, two days before the Derby, Gregson caught him a half-mile in 49[3/5], with a last quarter in 24 seconds. Perfect, the trainer figured. Jockey Bill Shoemaker, in town to ride Star Gallant in the Derby, told Arthur Hancock that Gato del Sol would win it. “He’s probably the only horse in the race who can go a mile and a quarter,” said Shoemaker, who was Cougar II’s regular rider.

This had certainly become the ideal year to have a 3-year-old sound of limb and with some ability who wanted to go that far. In the two weeks leading up to the Derby, the prohibitive favorite, Timely Writer, was stricken with a stomach ailment and it took emergency surgery to save his life. When Linkage jumped up and won the Blue Grass, he appeared to be the horse to beat, but his Maryland-based trainer, Henry Clark, resisted all entreaties to run in the Derby and shipped the horse to Maryland for the Preakness. (But Gato del Sol won’t be there, the distance being too short and the turns too tight to suit him.) That made Hostage, the well-bred winner of the Arkansas Derby, seem particularly formidable. On the Monday before the Kentucky Derby, however, Hostage broke down during a workout at the Downs and was retired. The result of this was that the field, expected to be 15 horses, swelled to 20, the maximum allowable under the rules. Nineteen started, after Rock Steady was scratched on race day.

Thus Gato del Sol, although he hadn’t won a race since last September, looked better day by day. There were serious doubts that Air Forbes Won, off his neck victory in the Wood Memorial, could get the distance. El Baba had won eight of 10, but his daddy, Raja Baba, wasn’t building them to go that far. Muttering hadn’t run since winning the Santa Anita Derby on April 4, and there were questions whether he had done enough to get 10 furlongs over the more tiring Churchill Downs surface. The axiom still holds: A horse has to be absolutely dead fit to win the Kentucky Derby.

Gregson obviously had his colt right where he wanted him. Moreover, he had Delahoussaye, a 30-year-old native of New Iberia, La., who is one of the nation’s leading riders. Last year his horses won $6,126,489, placing him fourth among all U.S. jockeys.

Delahoussaye’s ride in the Derby was supremely confident. Gato del Sol broke from the 18th post position, next to the extreme outside hole, and only Clyde Van Dusen (post 20 in 1929) had ever overcome a worse post to win. Clyde Van Dusen, though, had excellent speed and was on the lead after a quarter of a mile. Gato del Sol is a plodder. He cannot be rushed, because he tends to climb if he is, so Delahoussaye let him settle. Cupecoy’s Joy, the only filly in the Derby, rushed to the lead, with El Baba tracking her, and Air Forbes Won, the tepid $2.70-1 favorite, stalking him. Delahoussaye had his colt outside of horses, clear of trouble—”so I wouldn’t get trapped,” he said later—as he rounded the first turn. Gato del Sol started picking up horses as they raced down the backside. As the filly turned for home, El Baba moved to her right flank and Air Forbes Won came up outside of him. They turned for home three abreast.

Delahoussaye’s ride in the Derby was supremely confident. Gato del Sol broke from the 18th post position, next to the extreme outside hole, and only Clyde Van Dusen (post 20 in 1929) had ever overcome a worse post to win. Clyde Van Dusen, though, had excellent speed and was on the lead after a quarter of a mile. Gato del Sol is a plodder. He cannot be rushed, because he tends to climb if he is, so Delahoussaye let him settle. Cupecoy’s Joy, the only filly in the Derby, rushed to the lead, with El Baba tracking her, and Air Forbes Won, the tepid $2.70-1 favorite, stalking him. Delahoussaye had his colt outside of horses, clear of trouble—”so I wouldn’t get trapped,” he said later—as he rounded the first turn. Gato del Sol started picking up horses as they raced down the backside. As the filly turned for home, El Baba moved to her right flank and Air Forbes Won came up outside of him. They turned for home three abreast.

By now, though, Gato del Sol was rolling. As the leaders drove toward the eighth pole, El Baba, Air Forbes Won and the filly suddenly chucked the bit, and in a trice Delahoussaye had the lead. Laser Light and Reinvested made their runs but didn’t have enough. Gato del Sol had won his Derby, and so had Ed Gregson, Leone Peters and Arthur Hancock. Above all, it was the Kentuckian’s race. “This is the greatest thing to happen to me in this life,” Hancock said, as if he’d lived another. “I want to dedicate this Derby to Daddy.”